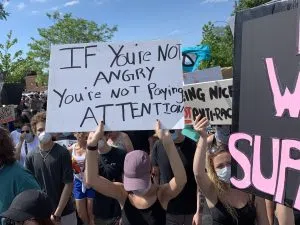

Following the police killing of George Floyd in May, the world underwent a racial awakening. Floyd, a Black man, was murdered by a police officer who kneeled on his neck for nearly nine minutes. The world erupted into protest for racial equality and an end to police violence.

From these protests, a new mantra arose.

“Defund the police.”

This was not an entirely new idea, as thinkers like Angela Davis had been writing about the abolition of the carceral state for decades, but the movement was now gaining traction. Calls to defund the police arose around the world, even here in London.

What does defunding the police really mean?

As interest in defunding the police grew, so too did confusion around it. The slogan suggested the complete disbanding of police departments, which seemed extreme to some. Many advocates of defunding the police do believe in the total abolition of police, but some merely believe that a portion of police funding should be re-allocated to social services.

In either case, funding re-allocation is key. Advocates for defunding the police believe that the money spent on policing would be better spent on housing, healthcare, and food security. By supplying people with these basic needs, advocates believe crime would naturally decrease and the need for police would be less.

London’s response

City Councilor for Ward 2, Shawn Lewis said that the city has heard the outcries for change, and has responded.

“We are already taking some pretty important first steps,” he said. “Most notably, we have actually created under the direct reporting mechanism to the city manager and council, a whole new directive at our city hall which is going to include a Black community liaison officer as well as an Indigenous community liaison officer.”

The Black and Indigenous community liaison officers will be working on anti-racism policy development for the city. Lewis said the hope is that this will lead to more inclusivity for the BIPOC community in London. The city has also expanded the eligibility for community grant programs, in order to open the door for more diversity-based organizations to access funding.

The city’s use of police officers in school is also under review at this time.

“The school resource officers are often a trigger for Black and Indigenous youth,” said Lewis.

Defunding vs reform

Evidence has shown that police reform as we know it hasn’t been entirely effective in combating anti-Black racism. That is why cries for funding re-allocation have grown more popular than the standard cries for diversity training and body cameras. But Lewis said he sees the merit in some reform programs.

“Some of the training is important,” he said.

He admitted that changing police funding is also not usually handled at the municipal level.

“The city councils do not have line-by-line control over our police budgets,” he said. “The police services board has that control. They submit us their budget, and at the end of the day, we have to pay what they ask for.”

Where things are going

Although changes to funding are difficult to coordinate, and may take several years to take effect, London’s police department has heard the cries for change.

“Even the London Police Services have a preliminary response,” said Lewis. “The police budget that was submitted to us in the Spring of 2020 was originally higher. And then the police came back to us, ‘we are willing to reduce our budget, we are willing to reduce our ask.”

Lewis said the police asked that funding be used on community housing programs, which council honoured.

While Lewis admitted the steps are small, he said changing the perception of police is a long road. But it’s a road that the city of London is prepared to go down.

Comments