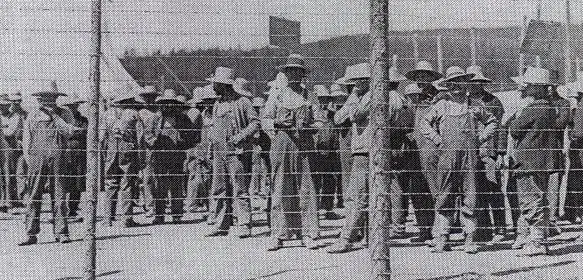

Camp 33 in Petawawa Ontario, where many Italian civilians were interned. Provided by the Petawawa Heritage Village.

When Italian dictator Benito Mussolini entered the Second World War on the side of Germany, the world trembled in fear.

Not only was it frightening for those fighting on the battleground, but for those living abroad as well.

It’s a widely known fact that German and Japanese Canadians were interned in camps for suspicion of fascist sympathies, but the internment of Italian – Canadians is almost entirely unknown.

On June 10, 1940, Italy declared war on Britain and France. As such, the Prime Minister of Canada, William Lyon Mackenzie King, authorized the RCMP to apprehend and intern Italian civilians. 600 Italian men were taken from their homes and put into camps on mere suspicion of fascist sympathies. None were ever criminally charged.

One of those men was my great, great grandfather, Crescenzio Pascucci. Like the history of Italian internment, I never knew of his existence. So I set out to uncover the truth behind this buried history. My first stop was my grandparents house to speak with my Grandfather, Chris D’Avino, about Pascucci.

“My grandfather was always ambitious. When he was refused land in Italy for the purpose of starting a vineyard, Crescenzio got up and came to Canada,” said D’Avino.

“He came here as a veteran of the First World War, fighting for Italy. During the time of the Second World War, I vaguely remember my mom saying he was interned. I’m not sure why he was declared an enemy of the state, as he fought on the same side as Canada during the First war,” he said.

As my grandfather grew older, he began to date my Grandmother, Antonietta.

“I remember him taking me to see Crescenzio at Sunnybrook Hospital. He was taken care of in the Veteran ward of the hospital, as the Canadian government recognized him for his service,” she said.

“He was so happy to see me. I remember him saying, ‘Chris, you’re the first person to bring a girl to see me!’ Then he gave me a prayer book, and he said, I want you to always keep this by your side. I still have that book.”

Near the end of Pascucci’s life, he’d often visit my grandparents to see my father Tony D’Avino, a newborn at the time.

“He always played with him for hours on our couch, and he would say the sweetest things, just the sweetest things to your father,” said Antonietta.

A veteran of the First World War, a dreamer, and a sweetheart. How did the Canadian government determine Crecenzio Pascucci was an enemy of the state?

To get background, I decided to ask Michael O’Hagan, a graduate student at the University of Western Ontario, who’s research is in POW’s during World War II.

“The Government felt they had to take steps because national security was at risk. They though it was easier to detain hundreds suspected of being fascists rather than take the time to interview and determine proper detainees,” he said.

As we look back on history, it turned out this wasn’t the best option.

“They very quickly realized these Italian men didn’t support Mussolini, they weren’t Nazis, they just plain and simply weren’t Fascist,” said O’Hagan.

“Many of them wanted to Enlist to fight for Canada as a lot of these Italian’s were Canadian citizens,” he said.

So how did internment affect these men and their families?

“Well, many of them felt betrayed by their country. There was lots of embarrassment, lots of anger. Once they were released, many of these men didn’t share their stories, as they just wanted to forget their time in the camps,” said O’Hagan.

Over the years, the Canadian government focused many efforts on apologizing towards Japanese Canadians.

“But no formal apology was ever made to the Italians. That’s a large reason as to why Italian internment isn’t commonly known. How can we teach our young Canadians in history classes if our own teachers aren’t aware of this happening?” said O’Hagan.

To this date, the closest the Federal government ever came to apologizing was In 2009, Liberal MP for Saint Léonard-Saint Michel, Massimo Pacetti, introduced Bill C-302 in the House of Commons. The bill called for the creation of a foundation to develop educational materials on Italian Canadian history. But the bill was never passed.

So is there anyplace in Canada preserving this buried history? Well, as I continued my research, I found out that an exhibit was on display at the Columbus Centre in Toronto. I got in touch with Flavio Belli, an art consultant for the Columbus Centre. He offered me information about his grandfather, Angelo Belfanti.

600 Italian men were interned during the Second World War. All the names are on display at the Columbus Centre in Toronto in their honour.

“He opened a restaurant in Toronto called Angelo’s, which was performing quite well. During the War, the RCMP accused Angelo of holding secret fascist meetings in the basement of the restaurant, so they arrested him and interned him at Camp 33 in Petawawa,” said Belli.

“I don’t believe my grandfather ever actually held meetings, as he wasn’t very political. All Angelo ever wanted to do was be in business, but the government sabotaged him.”

The Columbus Centre is currently undergoing heavy renovations, and has since removed their exhibit. but a new one is set to open at The Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg.

“It’s vital we keep our history preserved, as it’s not just important to Italians, but to Canadians. We must educate Canadians about the impact this had on Italian families in order to prevent history from ever repeating itself,” said Flavio Belli.